Dates of Birth and Death

September 25, 1864 - September 13, 1964Birthplace

Cambridge, MassachusettsEducation

- Cambridge High School, 1877–82

- School of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, 1882–86

- Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1888–90

Affiliations/Firms

- Allen and Kenway, Boston, Mass., 1890–92, draftsperson

- Lois L. Howe, Boston, Mass., 1894–1913

- Howe & Manning, Boston, Mass., 1913–26

- Howe, Manning & Almy, Boston, Mass., 1926–37. 101 Tremont Street, Boston, Mass., 1926–37 Practice transferred to Eleanor Manning O’Connor

Professional organizations

- A.I.A.

- Council of the School of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, 1897–1931

- Housing Association of Metropolitan Boston, 1932–47

Awards, honors and press

- Women’s Building, Chicago World’s Fair, 1893, Second Prize

Location of architect’s archive

Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Institute Archives and Special Collections. The Cambridge Historical Society.Related websites

Biography

Written by Andrea Jeanne Merrett, Columbia University

Howe, Lois Lilley (1864–1964), was the founding member of Howe, Manning and Almy, Boston’s first all-female architecture partnership, and only the second such practice in the United States. She was also the first woman to be selected as a fellow of the American Institute of Architects.

When the firm of Howe, Manning and Almy sent out a notice announcing the end of their partnership on September 1, 1937, William Emerson (1873–1957), dean of Architecture at MIT, wrote to the partners:

You three have made history for our profession, and the passing of Howe, Manning and Almy as a firm leaves a gap in our numbers that can scarcely be filled. . . . Each of you in your different ways and in different degrees have given other women hope and confidence. You have blazed a path which is the easier for them to follow, built a reputation and set a standard that they may well strive to emulate. [1]

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, it was remarkable to be a woman in architecture. It was an even greater achievement to have a successful firm run by three women. The office of Howe, Manning and Almy was well recognized in the press and by the architectural community in Boston. The success of the firm was due in great part to the perseverance of Lois Lilley Howe, who founded the office in the 1890s.

Early life and education

The MIT Museum and Florence Maynard

Howe was born in 1864 to Dr. Estes and Lois Lilly White Howe in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where she lived her entire life. Among her earliest recollections Howe remembers clambering around a construction site near her home, where the workmen called her “the little superintendent.” This fascination with construction was likely an early sign of her interest in architecture, although she was initially discouraged from studying architecture. In 1940, she wrote, “Always interested in houses, I had wanted to be an architect but had been suppressed by my pastors and masters on the ground that I could not be an architect because I was a woman.” [2]When her father died in 1887, after suffering financial losses from his real estate speculations during the recession of the 1870s, Howe’s mother sold the home where they were living and constructed a new house for the family. The old house had a straight staircase which the new owner, Mrs. Francis G. Peabody, sister-in-law to the architect Robert Swain Peabody, wanted to remodel. Howe was able to propose a successful solution even after Robert Peabody declared that it would be impossible to redesign the stair. This experience and the time spent on the construction site of the new house, designed by Cabot and Chandler, contributed to Howe’s decision to pursue architecture as a course of study.

In 1888, Howe entered the two-year program in architecture at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. After studying at Cambridge High School, Howe spent four years (1882–1886) at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston studying drawing and design rather than studying at the Harvard Annex (later Radcliffe College), as most of her classmates had done. At MIT, Howe was the only woman in a class of sixty-six and only one of two women in the school. While there, she helped found MIT’s first women’s student group, Eta Sigma Mu, which later became the sorority Cleofan. [3] In 1890, she completed the diploma, the same year that Sophia Hayden also graduated from the four-year program. [4] After finishing at MIT, Howe was assisted by an “interested friend” in finding employment in the office of Allen and Kenway, where she worked as a draftsman from 1890 to 1892. [5]

When the Board of Lady Managers for the Women’s Building at the World’s Fair in Chicago launched a competition in 1891 for the building, Robert Peabody, a lifelong supporter of Howe, encouraged her to enter a design. [6] The first prize was awarded to her friend and classmate Sophia Hayden, and Howe received $500 for second prize. This money allowed her to travel in Europe with her mother and sister for eighteen months, starting in July 1892. She returned the United States in October 1893, when she visited the Exposition before being given her first commission, the design of a house for a recently married friend. [7]

Career

Howe came from an old and prosperous Cambridge family, and her connections helped her to secure work. A female architect was more likely to receive commissions from friends and family members than from strangers, especially early in her career. [8] The first few years were a struggle, and it is possible that she supplemented her practice by other work. By 1900, however, Howe had established her firm on Tremont Street in Boston and she was soon busy with commissions for renovations and new houses.

During the early part of the twentieth century, it was not uncommon for women practicing architecture to specialize in residential work. Stereotypes about women and their close association with the domestic sphere limited the options for female architects. While these attitudes were a disadvantage for going after other types of projects, they were also something that Howe and her partners capitalized on. An unidentified newspaper clipping about the firm reported that their slogan was “the woman’s touch in architecture.” [9]

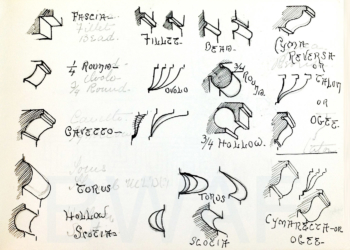

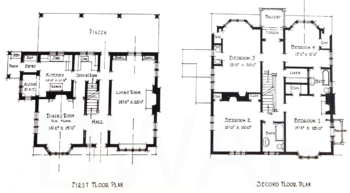

For over forty years, Lois Lilley Howe built a reputation for thoughtful design and well-constructed buildings. In her early career she mostly designed and renovated large houses for wealthy families with servants. From 1890 to the 1920s, Revivalist architecture was popular among New England’s upper classes. Howe mastered the Colonial Revival and Georgian Revival styles through careful research. During her travels around the region, she took numerous photographs and made measured drawings of buildings and architectural details. [10] Some of these drawings were eventually published in Details from Old New England Houses. [11]

In 1901, Peabody nominated Howe to the American Institute of Architects, where she was made a member, the second woman after Louise Blanchard Bethune. It is possible that Howe was elected to the AIA because her first name, Lois, was confused for Louis. [12] Her election to the AIA was particularly notable in Boston at the time, where women were not allowed to be members of the Boston Society of Architects, a requirement for AIA membership. Howe was also a trailblazer when she became a Fellow of the AIA in 1931, the first woman to be elected to this honor. [13]

Howe often hired female graduates from MIT to work as draftsmen in the office. By 1913, her practice had grown enough for her to ask one of those graduates working for her, Eleanor Manning, to become a partner. Manning brought to the firm a concern for public housing and urban planning, and with her addition to the practice, and a change in demand following World War I, the firm began focusing on more modest homes and housing complexes. In 1913, the partners contributed a design to McCall magazine’s Small House Series, and later published small house plans in House Beautiful and Architecture. [14] In 1924, the town planner John Nolen asked Howe and Manning to be involved in the design of Denny Place just outside Cincinnati. Theirs was one of twenty-six firms hired to build houses in the new planned community for working-class families. Their design used local stone, which was both economical and helped the houses blend into the landscape, an aspect Nolen emphasized in the master plan. [15]The project was published in Architecture in 1926, and Howe and Manning’s design received special attention. [16]

By 1926, the firm was doing so well that Howe and Manning asked Mary Almy to join the practice. Like Howe, Almy came from an old Cambridge family, and her connections brought many commissions to the firm. These included a house for Almy’s younger brother, Charles, and one for her parents. The Charles Almy Jr. House received attention in the press both for its design and because it became the temporary home of Governor Joseph B. Ely. [17] The firm continued to work in the Colonial and Georgian Revival styles for most of their private house designs. The partners also were recognized for their Cape Cod style houses. The same year that Almy joined the firm, they won a national wide competition for a Cape Cod house, sponsored by the Cape Cod Real Estate Board. The firm remained busy until the early 1930s, when the effects of the Depression made it harder for them to find work.

All three partners participated in various associations related to their work. Howe was on the planning committee of the Architect’s Small House Bureau and the housing committees for MIT’s Women’s Association and the Business Women’s Club of Boston. She was also involved with the Boston Society of Architect’s Small House Service Bureau, and the AIA’s Committee on Small Houses. This interest in housing continued after her retirement when Howe became a member of the Board of Directors of the Housing Association of Metropolitan Boston.

By the time Howe, Manning, and Almy disbanded in 1937—Howe was seventy-three at the time—they had completed over four hundred projects. [18] Howe lived for another twenty-seven years. Although she never married or had children, she was very active in the Cambridge and Boston communities. In addition to the committee work during her career, she continued to participate in local associations after retiring. To list a couple of her involvements, Howe was active with the Boston Society of Arts and Crafts and with the Cambridge Historical Society. [19] Howe died in 1964, less than two weeks before her hundredth birthday.

Major Buildings and Projects

Howe, along with her partners Eleanor Manning and Mary Almy, completed over four hundred projects, mostly consisting of houses and home renovations. Projects include:

- F. J. Garrison House, Pelham Road, Lexington, Mass., 1900

- Burrage House, Beech Street, Brookline, Mass., 1904

- Anne M. Paul House, Newburyport, Mass., 1912

- Cornish House, Fayerweather Street, Cambridge, Mass., 1916

- Lucy Stone Hospital, Boutwell Street, Dorchester, Mass., 1918

- Community Service of Boston, Army and Navy Club, 10 Park Street, Boston, Mass., 1920

- Eugenia Frothingham House, Grey Gardens, Cambridge, Mass., 1922

- Mariemont housing development, Denny Place, Cincinnati, Ohio, 1923

- McCall’s Magazine, house plans, 1923

- Cape Cod Competition, house design winner, Hyannis, Mass., 1926

- Charles Almy Jr. House, Coolidge Hill, Cambridge, Mass., 1926

- James Morgan House, Prescott Road, Lynn, Mass., 1932

- A complete list is available in Doris Cole’s The Lady Architects: Lois Lilley Howe, Eleanor Manning and Mary Almy, 1893–1937 (New York: Midmarch Arts, 1990).

Notes

1 Letter to Howe, Manning and Almy from William Emerson, September 5, 1937. Records of Howe, Manning & Almy, Inc., and the Papers of Lois L. Howe, Eleanor Manning O’Connor, and Mary Almy, MC 9, Series 1A, Box 1, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Institute Archives and Special Collections, Cambridge, Mass..

2 “Lois Lilley Howe—M.I.T. ’90,” recollections written in 1940 for fifty-year class reunion (which she was unable to attend). Records of Howe, Manning & Almy, Series 3, Box 4.

3 “Lois Lilley Howe—Biographical Note,” Records of Howe, Manning & Almy.

4 Sophia Hayden was only the second woman to graduate from the four-year program at MIT. The first, according to an announcement of Hayden and Howe’s prizes for the Women’s Building at the Chicago World’s Fair, was a Miss Rockfellow, who graduated in 1888. “Two Successful Girls,” March 26, 1891, Records of Howe, Manning & Almy, Series 3, Box 1.

5 “Lois Lilley Howe—M.I.T. ’90,” Records of Howe, Manning & Almy. According to Gail Morse, this person was likely to be either Chandler or Robert Swain Peabody. Gail Morse, “‘The Firm’: A Study of the First Women’s Architectural Firm in Boston: Howe, Manning and Almy,” B.A. thesis, Boston University, 1976, accessed August 6, 2013, https://open.bu.edu/xmlui/handle/2144/6073.

6 “Lois Lilley Howe—M.I.T. ’90,” Records of Howe, Manning & Almy.

7 Morse, 36.

8 Morse, 37. Morse suggests that Howe might have worked part-time as a librarian for MIT’s architecture department, 36.

9 “Lady Architects Scorn ‘He’ Houses,” circa 1936, Records of Howe, Manning & Almy, Series 1A, Box 1.

10 Many of her photographs are archived at the Cambridge Historical Society, https://www.cambridgehistory.org/library/howe.

11 Lois Lilley Howe and Constance Fuller, Details from Old New England Houses (New York: Architectural Book Publishing Co., 1913).

12 Sarah Allaback, “Howe, Lois Lilley (1864–1964),” The First American Women Architects (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2008), 104.

13 Louise Blanchard Bethune was the first Fellow of the AIA, an automatic appointment when the Western Association of Architects, of which she was a member, was absorbed by the AIA in 1889. “The A.I.A. Historical Directory of American Architects.” https://public.aia.org/sites/hdoaa/wiki/.

14 “Portfolio of Small Houses,” House Beautiful (May 1929): portfolio 1.

15 For more about the project in Mariemont, Ohio, see Morse, 60–63.

16 “Mariemont—A New Town,” Architecture 54 (September 1926): 247–78

17 “Three Women Designed House in Which Gov Ely Will Live,” unidentified newspaper article, N.D. Records of Howe, Manning & Almy, Series 1A, Box 1. The Charles Almy Jr. House was also published in “Portfolio of Small Houses,” House Beautiful (May 1929): portfolio 1.

18 For a list of projects, see Doris Cole and Karen Cord Taylor, The Lady Architects: Lois Lilley Howe, Eleanor Manning and Mary Almy, 1893–1937(New York: Midmarch Arts, 1990).

19 Morse, 68.

Bibliography

Writings by Howe

“An Alumna’s Architectural Career.” Technology Review 66, no. 2 (December 1963): 21, 38.

An Architectural Monograph: The Colonel Robert Means House at Amherst, New Hampshire. White Pine Series of Architectural Monographs 13. New York: R. F. Whiteheat, 1927.

“Memories of Nineteenth Century Cambridge.” Proceedings of the Cambridge Historical Society 34 (1952): 59–76.

“Serving Pantries in Small Houses.” Architectural Review 14 (March 1907): 31–33.

With Constance Fuller. Details from Old New England Houses. New York: Architectural Book Publishing Co., 1913.

Writings About Howe

Allaback, Sarah. “Howe, Lois Lilley (1864–1964),” The First American Women Architects. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2008.

Cole, Doris, and Karen Cord Taylor. The Lady Architects: Lois Lilley Howe, Eleanor Manning and Mary Almy, 1893–1937. New York: Midmarch Arts, 1990.

“House of Mrs. A. A. Burrage, Beach Road, Brookline, Mass.” American Architect and Building News 88 (July 15, 1905): 24, plate.

“Lois Howe: Portrait.” Architectural Forum 101 (July 1954): 116.

“Lois Lilley Howe.” In American Women, 1935–1940, edited by Durwood Howes, 430. Detroit, Mich.: Gale, 1981.

“Lois Lilley Howe: Obituary.” Progressive Architecture 45 (October 1964): 118.

Morse, Gail. “The Firm: A Study of the First Women’s Architectural Firm in Boston: Howe, Manning, and Almy.” B.A. thesis, Boston University, 1976.

Paine, Judith. “Pioneer Women Architects.” In Women in American Architecture, edited by Susana Torre, 66–68. New York: Whitney Library of Design, 1977.

Reinhardt, Elizabeth W. “Lois Lilley Howe, FAIA, 1864–1964.” Cambridge Historical Society Publication 43 (1980): 153–72.